The Life of Alfred Masters: A Historical Discussion About the First Black American Marine and his Service in the Marine Corps.

In 1942 the United States Marine Corps took the first steps towards integration. In fact, on 1 June 1942, Alfred Masters became the first Black American to be sworn into the Marine Corps. However, rather than him, another Black American is sometimes credited as being the first: Howard P. Perry. This article will examine why that is and then share the history of Masters in the service. Note: this article will contain words from unaltered historical sources that could offend contemporary readers.

The United States Marine Corps and its History

Back in the 1940s, the United States of America was segregated. In practical terms, this often limited opportunities for Black Americans and since the armed forces reflect the societies that create them, this meant that Black Americans served in dedicated units in the Army or that they could only serve within certain occupations in the Navy, such as messman or steward. In addition to this, the United States Marine Corps was a service for whites only. As war broke out in Europe and the United States prepared for war, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 8802 on 25 June 1941. This order detailed that racial discrimination in the government and in the defense industries was forbidden. It was the first step towards creating segregated units in the Marine Corps. After the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, when the Imperial Japanese Navy suddenly attacked and the Black American mess attendant Doris Miller distinguished himself in action, the United States became a participant in World War II. The war wasn’t just a distant series of events, but something that was brought to American shores. Production and recruitment were ramped up. Later, on 7 April 1942, Frank Knox, the Secretary of the Navy, issued a statement, which included that:

The Navy Department today announced that Negro volunteers will be accepted for enlistment for general service in the reserve components of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the U.S. Coast Guard. All ratings in those three branches of the Naval Service will be opened to them, and recruiting is to be begun as soon as a suitable training station is established. A public announcement will be made when actual recruiting gets under way.1

Furthermore, on 20 May the following announcement was made by the Navy Department:

MARINES ANNOUNCE PLANS FOR RECRUITING NEGROES IN USMC

The first battalion of Negroes, numbering about 900, will be enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve during the months of June and July, it was announced at U.S. Marine Corps Headquarters.

Those volunteers will form a composite battalion which is a unit including all combat arms of the ground forces composed of artillery, anti-aircraft, machine guns, tank and infantry, and including also billets for recruits who are skilled in various trades and occupations such as radio operators, electricians, accountants, carpenters, draftsmen, band musicians, riggers and blacksmiths.

Until a training center is ready for their reception recruits will be temporarily placed in an inactive duty status. The training center will be in the vicinity of New River, North Carolina where a large Marine Corps post is now located. As required, Negro recruits will be ordered directly from their homes to duty in this training area.2

As can be read, in June 1942, the recruiting of the first Black American Marines could start. It so happened that Alfred Masters by chance met a marine recruitment officer a few days before 1 June 1942. As described by his wife Isabell Masters:

On Saturday, May 30, 1942, Alfred and I happened to be on the elevator at the post office building in Oklahoma City with a Marine recruitment officer who asked Alfred if he wanted to be the first Black Marine.

Alfred had a good physique and good posture and was wearing his Langston University sweater, which motivated the recruiter to approach him. Of course, the answer was yes. Just prior to his enlistment, Alfred had received his draft papers from the Selective Service notifying him that he was being called for duty into the Army, and to report for induction into the military service.

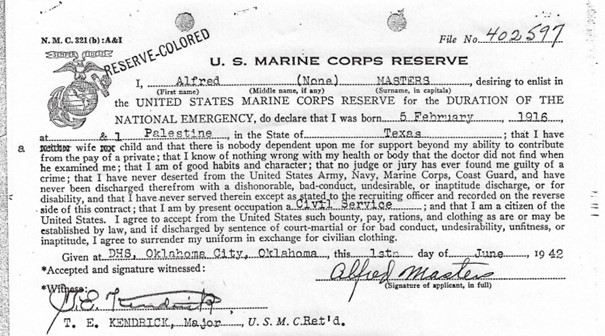

The recruiter then escorted us to the recruitment office. Once there, Alfred had to take a physical exam, and although he was 26 years old and a civilian employee in the Army Air Corps, I had to sign papers allowing him to enlist, stipulating that I, nor our child, were financially dependent on Alfred beyond what he could contribute from his pay as a private. After signing papers, the recruiter told Alfred to return to the post office ten minutes to midnight on Sunday night in order to be sworn in as the first Black Marine on Monday morning, June 1, 1942. He was worried that the states on the East coast would beat them at getting the first Black recruit due to the earlier time zone. […] When we arrived, the media was there, and among flashing lights of the Daily Oklahoman Newspaper, with me standing by his side, on Monday morning, June 1, 1942, one minute after midnight, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Alfred was inducted into the arm services as the first Black Marine by Major Thomas E. Kendrick.3

Alfred Masters was inducted on Monday 1 June 1942 at 00:01 hours in Oklahoma City. Later that same day, at 08:01 hours in Tennessee, George Thompson was inducted on 1 June. At the time, he was under the impression that he was the first Black American in the Marine Corps. That is, in the words of Isabel Masters, “until radio broadcast notified him otherwise.”4 As such, for a few hours, he thought that he had held the honor.

This image of Alfred Masters being sworn in was published on 2 June 1942 in The Daily Oklahoman.5

Another article, from The Black Dispatch, dated 20 June 19426. It clearly mentions Alfred Masters as the first Black American Marine. The enlistment Alfred Masters was publicized in Oklahoma.

Another article, from The Daily Oklahoman, dated 1 June 1942.7 It also mentions Alfred Masters as the first Black Marine.

Enlistment records of Alfred Masters, clearly showing the date: 1 June 1942.8 (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters)

Why do people Credit Howard P. Perry as the First Black American Marine?

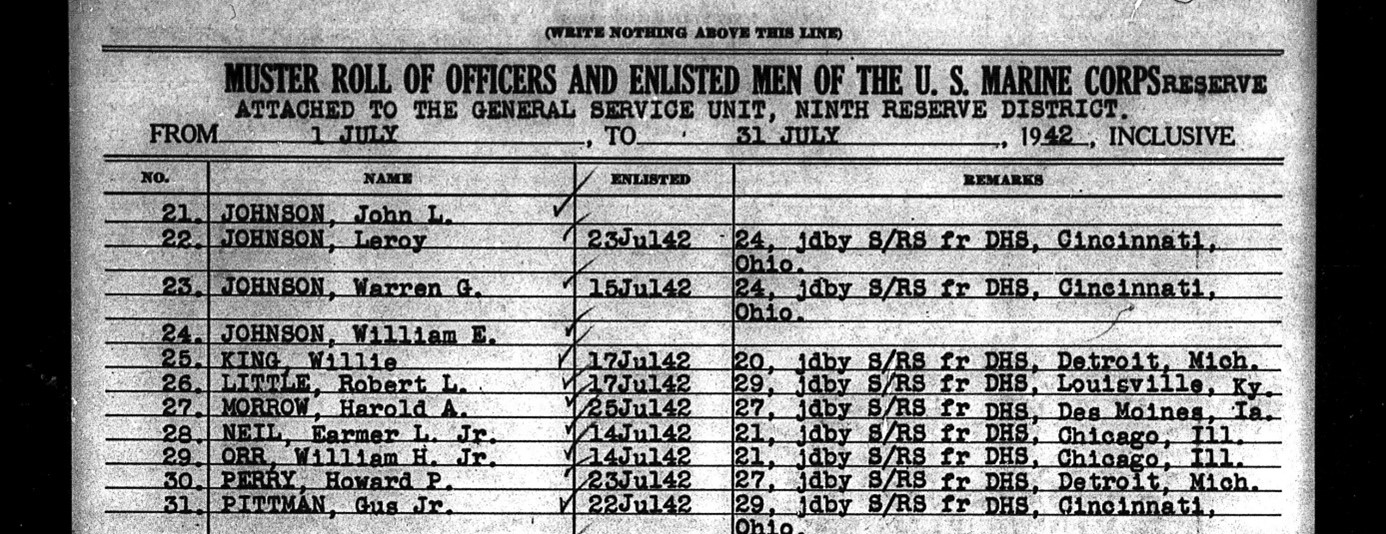

To strike immediately at the center of the issue: Howard P. Perry signed his enlistment records on 23 July 1942. Thus, he signed them more than 7 weeks later than Alfred Masters. This can be confirmed by the muster rolls, which are in possession of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Yet, in newspapers written during that time period, Perry is often credited as the first. As for example appeared in The Jackson Advocate of 22 May 1943:

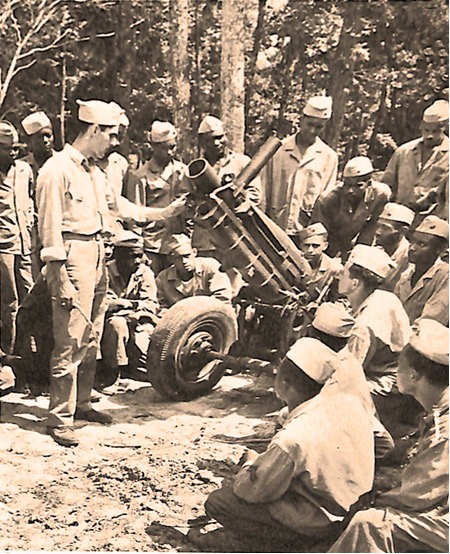

The images detail the activities of Black American marines at Camp Lejeune and the caption mentions: “Pvt. Howard P. Perry, first Negro to volunteer for Marine Corps service, is shown in the center.”10 Or The Omaha Guide of 4 September 1943:

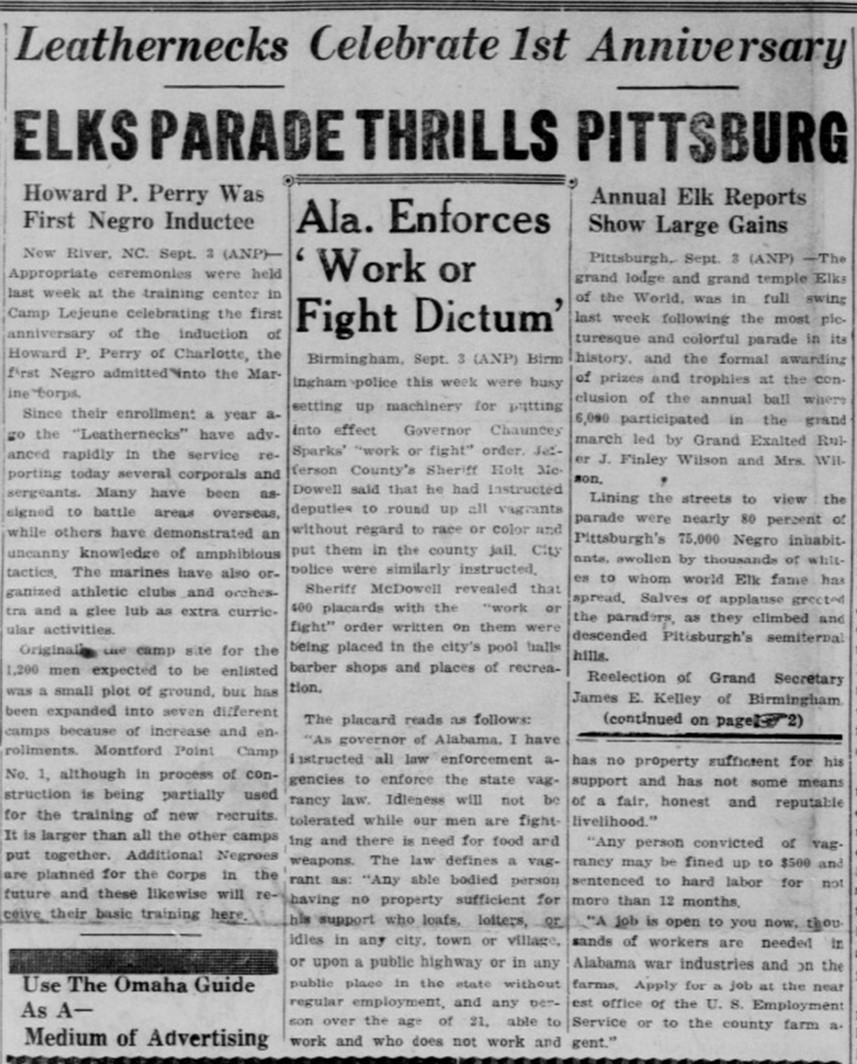

In the Omaha Guide of 4 September 1943, in the article "Leathernecks Celebtrate 1st Anniversary" it clearly mentions:

Howard P. Perry was First Negro Inductee […] Appropriate ceremonies were held last week at the training center in Camp Lejeune celebrating the first anniversary of the induction of Howard P. Perry of Charlotte, the first Negro admitted into the marine corps.11

In the Henderson Daily Dispatch, dated 19 September 1942, Howard P. Perry is again mentioned as the first Black American marine.12

Another complication in this historical error is that Alfred Masters arrived at the camp in November 1942. Media coverage, which featured the Black marines in training, had already written about it. This included crediting Howard P. Perry as the first Black marine.13 Thus, Perry received a lot of attention and even though the historical facts imply otherwise, word has already gotten out. Even if Masters wanted to rectify it, it would take a lot of time and effort.

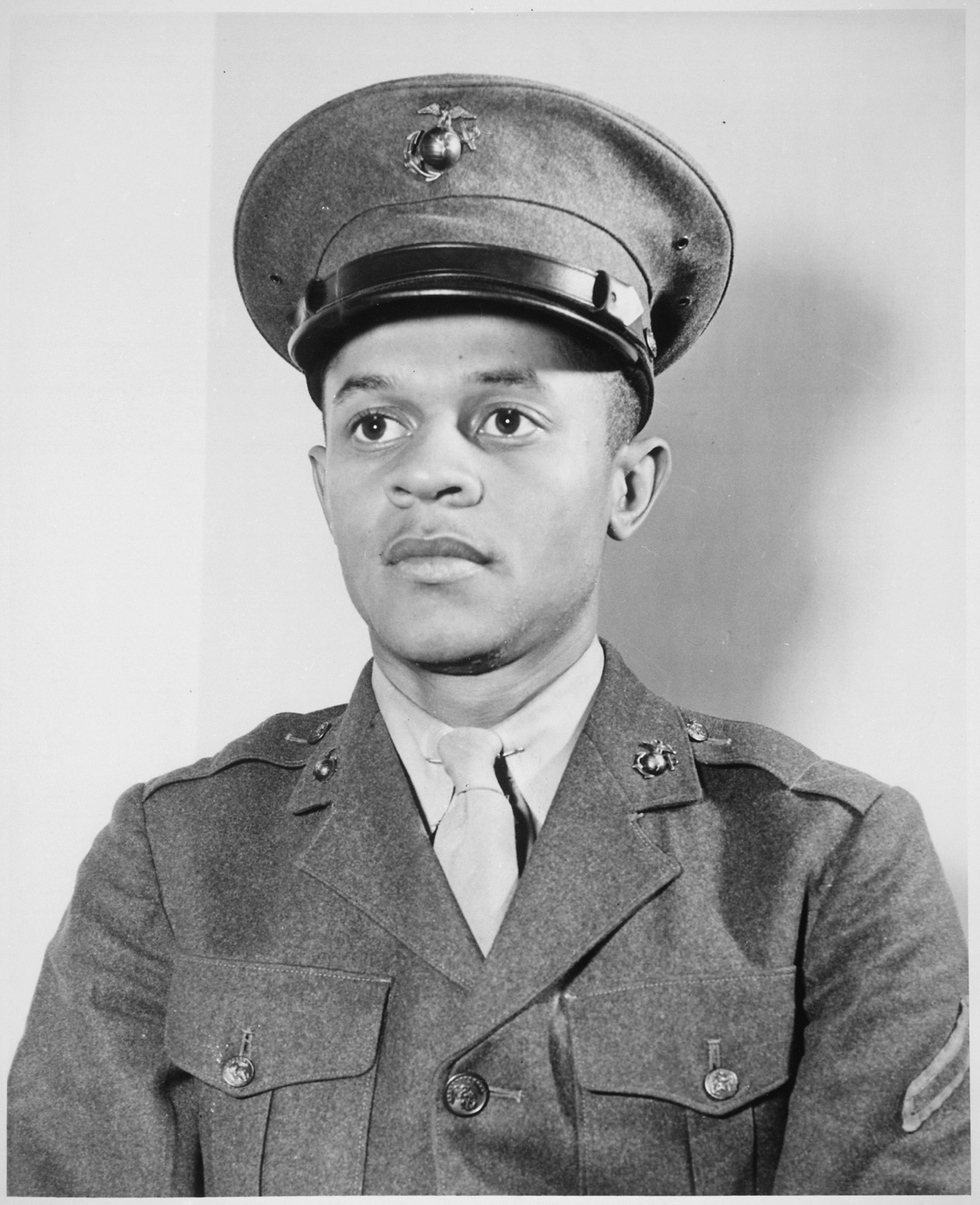

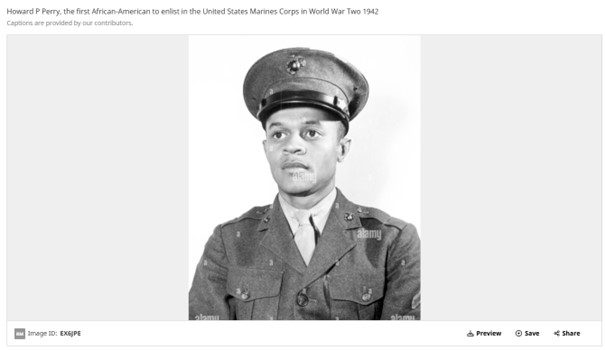

As such, the error didn’t just exist at that time, but also appeared to have slipped in the history writing itself. Often the following image is added in the history books, internet blogs or social media:

(Photograph of Marine Howard P. Perry at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, courtesy of National Archives: NAID: 535870) And the following text from the original caption:

Breaking a tradition of 167 years, the U.S. Marine Corps started enlisting Negroes on June 1, 1942. The first class of 1,200 Negro volunteers began their training 3 months later as members of the 51st Composite Defense Battalion at Montford Point, a section of the 200-square-mile Marine Base, Camp Lejeune, at New River, NC. The first Negro to enlist was Howard P. Perry shown here.14

Alamy still lists Howard P. Perry as the first Black American marine.15 This contributes to the error, because this image is easily made available to people. The problem is further compounded by social media with its visual-driven content. The error, with an image of Howard P. Perry attached or included, is then spread further. Now then, why is he credited as the first in so many sources? Take a look at a few examples. Errors also exist in African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, which lists: “Howard P. Perry, the first African American to enlist in the U.S. Marine Corps. Breaking a tradition of 167 years, the Marines started enlisting African Americans on June 1, 1942. (National Archives)”16

June 1. The U.S. Marine Corps breaks its 167-year tradition of being a whites-only section of the armed forces. Howard P. Perry is the first of 20,000 African Americans to serve in the marines during World War II. They will all be trained at Montford Point, North Carolina.17

“August 26. Howard P. Perry reports to Montford Point as the first-ever African American member of the U.S. Marine Corps. Some 12,738 African American marines will serve overseas during World War II.”18

While not incorrect, some history books, like Black Firsts, do correctly credit Howard P. Perry as “the first black to report” for duty.19 However, these books then don’t mention Alfred Masters at all. Thus, while getting part of the history correct, they omit the induction of Alfred Masters entirely and allow the historical error to persist.

Now, the error results from the fact that Howard P. Perry was the first off the bus to report for duty at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, on 26 August 1942. People would consider this to be the “first” marine. However, Perry was not the first to be sworn in, which was Alfred Masters. As such, this explains the error in the historiography. The distinction lies in timing and context. Alfred Masters was the first Black American to take the oath and be sworn into the Marine Corps. However, Howard P. Perry’s prominence as the first Black recruit at Montford Point led to him being erroneously identified in some accounts as the first Black Marine. Photographs of the Black marines in training, like the earlier mentioned images in the Jackson’s Advocate, were widely circulated at the time. These images of the Black marines in training had Perry at the center, which added to the confusion and overshadowed Masters’ earlier enlistment.

Historical documentation, related to the Marine Corps, generally does seem to accurately credit Alfred Masters as being the first Black marine. This includes the books and articles Blacks in the Marine Corps20, Guidebook for Marines21, USMC: A Complete History22. Thus, while the Marine Corps usually gets the history correct, it seems that the people outside of the corps are not always aware of Alfred Masters’ service.

The historical evidence clearly establishes Masters as the first Black American to enlist in the Marine Corps, with Howard P. Perry notable as the first recruit at Montford Point. While confusion persists in some accounts, military records and timelines affirm Masters’ rightful place in history. Both men, however, symbolize the courage and determination of Black Marines who broke barriers in a segregated military. Recognizing both Alfred Masters and Howard P. Perry is essential to understanding the broader context of the integration of African Americans into the Marine Corps. Their roles symbolize the groundbreaking efforts of early Black Marines who paved the way for future generations. Let us therefore honor the sacrifices of both men and give them the credit they are due.

So Who Was Alfred Masters?

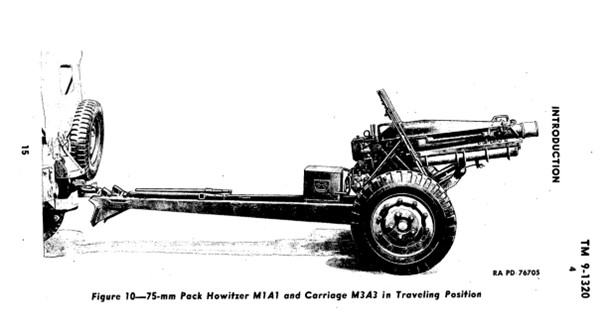

Alfred Masters (1916 – 1975) arrived on 17 November 1942 at Montford Point, a segregated training camp for Black Marines in Jacksonville, North Carolina. This camp became the training ground for the first Black American recruits in the Marine Corps, known as the Montford Point Marines. The conditions were challenging, and the Marines faced racism and segregation both within the military and in the surrounding communities. The Black soldiers were supposed to form a composite defense battalion: 51st Composite Defense Battalion. This meant that, unlike other defense battalions, it incorporated anti-aircraft artillery, artillery, tanks, and other special weapons. The unit was under the command of Colonel Samuel A. Woods Jr., who was generally liked by the marines under his command. At Montford Point, after completing recruit training, Masters served with the 75mm Pack Howitzer Battery.

On 28 May 1943, a recommendation by the new battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Floyd A. Stephenson, was approved, which stated that the Rifle Company (Reinforced) and the 75mm Pack Howitzer Battery would be detached. The unit would keep the 90mm antiaircraft guns and the 155mm artillery guns. Thus, on 7 June 1943, the 75mm Pack Howitzer Battery was separated from the 51st Composite Defense Battalion. Instead it would become the 7th Separate Pack Howitzer Battery. The reinforced rifle company became Company A, 7th Separate Infantry Battalion and the 51st Composite Defense Battalion became the 51st Defense Battalion.

Alfred Masters became a cook when the battery was out in the field on a hot, humid, and windy day. The group was told that a new assistant field cook was needed, and was asked if anyone knew how to cook. Alfred’s mother, Lettia Masters, had taught her children survival skills both inside and outside the home. Since Alfred wanted to get out of the inclement weather, he volunteered to cook. However, his commanding officer initially didn’t want to let Masters go, because of Alfred’s prowess in the field. But Alfred was the only one who could cook, and so he was reluctantly chosen for the duty.25 On 9 August 1943, Alfred Masters was transferred to Headquarters Company and followed training to become a military cook. This was a highly coveted function. As described by Charles L. Bryant:

Had to go to cook and bakers’ school when you became a cook to learn how to cook military style no matter whether you could already cook or not. Lasted 30-60 days. To become a mess sergeant, they would send you over to an area on the base called the Steward’s Branch. Went to school called a Stewards Baker’s School. Get you familiar with cooking military food. There was a different way you cook military food from the way you cook normal food. This is why they would send you to school. They didn’t care how good a cook you were, you had to go to that school first. Once you got out of boot camp, they put you over there and give you some on the job training. And the first thing you know it, you would be taking over one of the mess halls. The cook and bake school was the best thing you could do at that time because that was the only thing they had for you, other than training. Nothing else prepared you for the outside world back in that time other than cooks and bakers’ school. A lot of people tried to get into Cooks and Bakers’ School.26 On 25 August 1943, Masters was promoted to Assistant Cook. On 7 October 1943 he returned to the 7th Separate Infantry Battalion, where he served with the 7th Separate Pack Howitzer Battery. He received a promotion to Field Cook on 22 December 1943. A few days before, on 15 December 1943, the first group of men were transferred out of the 51st Defense Battalion and formed the 52nd Defense Battalion. On 20 March 1944 Masters was transferred to the 52nd Defense Battalion. He became Chief Cook on 15 July 1944. Charles L. Bryant explained Alfred’s duties as Chief Cook while attached to the 52nd at Montford Point before he left to go overseas : ALFRED ran the mess hall for the 52nd Defense Battalion. […] Alfred was a No. 1. [...] He had a 100 men under him. He ran the whole show: cooks, bakers, messmen, people who cleaned up the mess hall. Planned the menus. He would plan the first one and then teach to the next one. They would come up and he would view it, and if he didn’t like it, they would redo it again. But he was overall in charge. He would train on the field once a week.27 Masters would continue to serve with the 52nd Defense Battalion. On 21 August 1944, the 52nd Defense Battalion left camp to go overseas. On 15 September 15 at Camp Pendleton, on his way overseas, he became an unofficial Technical Sergeant, and on 1 November, he was officially promoted.

The unit arrived in Majuro Atoll on 15 October 1944 and he continued to serve there until 9 March 1945. As described in Blacks in the Marine Corps:

Lieutenant Colonel Moore's detachment at Majuro, in addition to its air defense duties, found itself acting as reconnaissance Marines. Monthly after the detachment arrived, patrols of 60-65 men from the firing batteries would board naval landing craft and check out the atolls, mostly Erikub and Aur, which lay between Majuro and the nearest Japanese bases. These two-to-six day excursions were generally uneventful, although a Battery C patrol to Tabal Island in December brought in three Japanese prisoners the natives had taken, and a Battery D patrol to Aur in January brought back 186 natives to be resettled at Kwajalein.29

Alfred Masters arrived on 23 March 1945 in Guam. On the island, the 52nd Defense Battalion set up camp and there were still hundreds of armed Japanese troops on the island who had remained after the island had been recaptured in July and August 1944. These Japanese troops were armed, and although not an effective combat unit, they still formed a potential threat. However, the Japanese soldiers were more interested in foraging and staying alive than fighting. The 52nd Defense Battalion sent out small 10-man patrols or set up ambushes. The battalion encountered the enemy for the first time on 1 April, when they killed one of two enemy soldiers found in the area around the camp.

During his stay on Guam, in a story that he told his children, he related how one morning six of his men were going to the mess tent to prepare for breakfast.30 He warned them to take along their rifles, but they deemed themselves safe in the camp and didn’t do so. It wasn’t long before he heard commotion and then saw the men running away from the mess tent, yelling: “We’re being invaded by the Japanese! We’re being invaded by the …” Masters looked beyond the soldiers and saw a single scrawny Japanese soldier running away. He carried a crate of food (K rations) above his head. The whole scene made Masters burst out in laughter.31

Alfred Masters was liked by his men. As Charles Davenport, who served alongside Alfred Masters, said about him: “Alfred was a lively person”32 and “He was a leader. No flunky or mess up.”33

On 16 November 1945, Masters left Guam. In total, he served 14 months and 19 days overseas in the Pacific with the 52nd Defense Battalion. He was discharged in December 1945. After serving his country, he still encountered segregation. As described:

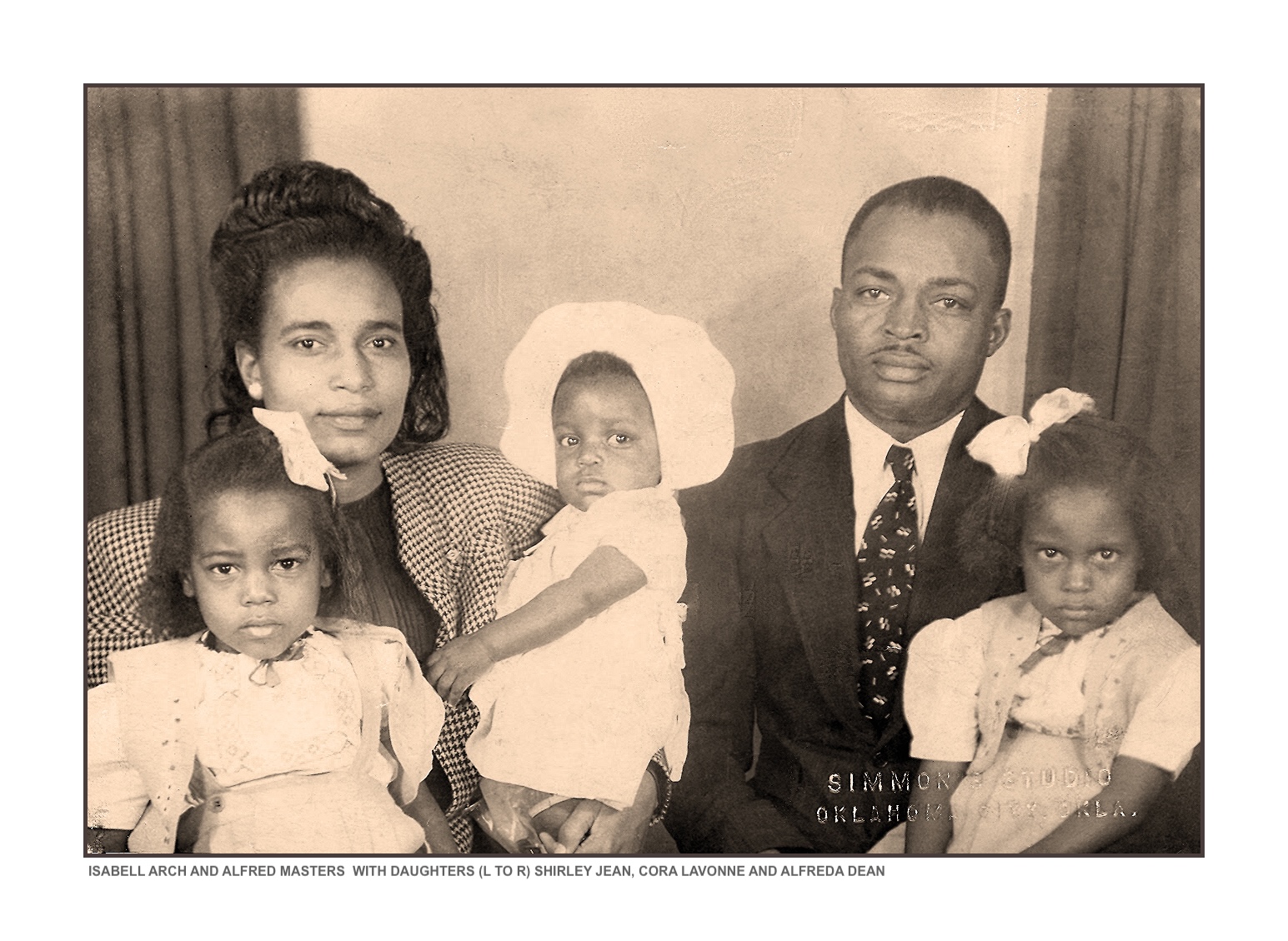

After being discharged, Alfred immediately made his way to San Diego and boarded the train for Oklahoma City in order to be home in time to spend Christmas together with his wife, Isabell, and their three children, Shirley Jean, Alfreda Dean, and seven-month old infant daughter, Cora Lavonne, whom he had only seen in a photograph. The train ride from California to Oklahoma was very enjoyable and full of good cheer. He had fun laughing, talking, and sharing family and war tales with two White marine sergeants who were also traveling home to be with their loved ones for Christmas. The spirit of the season and freedom reverberated throughout the passenger train car.

Upon arriving at a stop in his Jim Crow home state of Oklahoma, Alfred was told that there would not be any colored passenger train cars to take him to his final destination of Oklahoma, City for several days. Not being home for Christmas was not an option for Alfred. What was once a festive mood changed to a discordant scrambling for ways and means of achieving his goal. Alfred insisted that he be allowed to ride in the mail car the remainder of his journey home. After initial denial and argument, they acquiesced, and Alfred, after serving his Country, had to continued home sitting on a milk can in the mail car. He arrived home December 25, 1945.34 However, he arrived home and one of the earliest recollections of Alfreda Masters about her father was of him: […] standing in the doorway in his uniform on Christmas night, 1945, when he returned home from the service. I was almost three years old. Shirley and I (Cora was a baby) didn’t much like waiting all day to open our Christmas presents. But that night, our father rode us around on his back playing horsy. Shirley and I had so much fun we soon forgot about our toys. Our father was our “bestest” gift that Christmas night.35

Alfred Masters always referred to himself as a gunnery sergeant, not a tech sergeant, and he kept his gunnery sergeant stripes. He was dismayed that his discharge papers didn’t list him as having served in a war zone, even though his unit had to go on patrols and mop up the last Japanese soldiers on Guam. Post-military service, Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters became Professor Masters and for five years traversed counties in his home state of Oklahoma teaching agricultural farming to returning WWII veterans. He and his wife Isabell divorced in 1947 and he remarried Mary Hendricks in 1949 and they moved to Cleveland, Ohio around 1951. While living in Cleveland, they had five children, and Alfred, among other side jobs, worked as a caster in a steel factory as well as became a union representative in the UAW. His proudest accomplishment as a union representative was negotiating a scheduled or unscheduled short workweek guarantee of 32 hours at average pay.

In 1965 Masters moved his family to Las Cruces, New Mexico where his mother, Lettia lived. A year later he moved his family to a 320 acre cotton farm in the area of Vado, New Mexico and worked it with his five children like his mother did with him and his siblings in Seminole County, Oklahoma. Alfred Masters suffered a heart attack on 16 June 1975 and passed away at 59 years old. He is buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery in El Paso, Texas. Howard P. Perry, who coincidentally also served as a cook, was discharged in December 1945 and he died on 13 August 1986. Isabell moved to California in 1949, taught elementary school, had three additional children, and in 1970, while working on her M.A. Degree, she and her six children were featured in Ebony Magazine for all attending college at the same time. She eventually became an evangelist, earned a Ph.D at 68, and at 71 became a perennial candidate for President of the United States from 1984 to 2004 (more than any woman in history) to teach her children not to limit their horizons. Her daughter, Shirley Jean, was her running mate in 1996 and her daughter, Alfreda Dean, was her running mate in 2004. Her daughter, Cora Lavonne, became the second wife of D.C. Mayor Marion Barry and became very influential in improving the self-esteem of Black children in the D.C. area. Isabell died on September 11, 2011 and is buried in Topeka, KS. I hope you found this article informative!

Sources:

“Alfred Masters Overseas Tour of Duty” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

“Alfred, The Cooks, And The Scrawny Japanese (Related By Alfred Dan Masters, Son)” (courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

“An Outline Of Family Togetherness And Isabell’s Goings, Comings, And Doings During Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters’ WWII Military Service (Sourced From Alfreda’s Baby Book And Isabell’s Autobiography)” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

“Charles Davenport, Gunnery Sergeant/Acting Master Sergeant, Recollections Of Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters, Excerpts From An Interview With Alfreda Masters” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

“Excerpts From An Interview With Charles L. Bryant, USMC, Retired, Age 72” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

“How Alfred Masters Became The First Enlisted Black Marine By Dr. Isabell Arch Masters”, Prepared By Alfreda D. Masters.

Alamy, Howard P Perry, the first African-American to enlist in the United States Marines Corps in World War Two 1942, Image ID: EX6JPE, link: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-howard-p-perry-the-first-african-american-to-enlist-in-the-united-84968982.html (checked 13 January 2025).

Guidebook for Marines (2009).

Henderson Daily Dispatch, “First Negro Marine”, 19 September 1942.

Hoffmann, Jon T. (ed.), USMC: A Complete History (2002).

Masters, Isabell Arch, “Not For Myself But For Others”.

Navy Department, “Marines Announce Plans for Recruiting African-Americans”, 20 May 1942, link: https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Marines-Announce-Plans-for-Recruiting-African-Americans/ (Checked 14 January 2025).

Navy Department, “Navy to Accept African-Americans for General Service”, 7 April 1942, link: https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Navy-to-Accept-African-Americans-for-General-Service/ (checked 14 January 2025).

Photograph of Marine Howard P. Perry at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, courtesy of National Archives: NAID: 535870, National Archives and Records Administration, link: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535870 (checked 13 January 2025).

Record Group 127: Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Series: Muster Rolls and Personnel Diaries, July 1942 - Vol 3, NAID: 195486951, National Archives and Records Administration.

Shaw, Henry I. Jr., and Ralph W. Donnelly,* Blacks in the Marine Corps *(2002).

Smith, Jessie Carney, *Black Firsts: Groundbreaking events in African American history (*2009).

Sutherland, Jonathan D., *African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia (*2004).

The Black Dispatch, “Oklahoma First Negro Marine Enlistment”, 20 June 1942.

*The Daily Oklahoman, “*First Negro Marine”, 2 June 1942.

The Daily Oklahoman, “Marines Sign First Negro”, 1 June 1942.

The Jackson Advocate, “Negro Youths Prepare To Live Up To Glorious Marine Tradition”, 22 May 1943.

The Omaha Guide, “Leathernecks Celebrate 1st Anniversary”, 4 September 1943.

U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, “Alfred Masters”, File No. 402597 (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters).

War Department, TM 9-1320, War Department Technical Manual, Ordnance Maintenance, 75-mm Howitzers and Carriages, April 1944.

Footnotes

-

Navy Department, “Navy to Accept African-Americans for General Service”, 7 April 1942, link: https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Navy-to-Accept-African-Americans-for-General-Service/ (checked 14 January 2025). ↩

-

Navy Department, “Marines Announce Plans for Recruiting African-Americans”, 20 May 1942, link: https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/Frequently-Requested-Topics/Historical-Documents-Orders-and-Speeches/Marines-Announce-Plans-for-Recruiting-African-Americans/ (Checked 14 January 2025). ↩

-

Courtesy of Alfreda Masters & Isabell Arch Masters, “Not For Myself But For Others”. ↩

-

Masters, “Not For Myself But For Others”. ↩

-

The Daily Oklahoman, “First Negro Marine”, 2 June 1942. ↩

-

The Black Dispatch, “Oklahoma First Negro Marine Enlistment”, 20 June 1942. ↩

-

The Daily Oklahoman, “Marines Sign First Negro”, 1 June 1942. ↩

-

U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, “Alfred Masters”, File No. 402597 (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

Record Group 127: Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Series: Muster Rolls and Personnel Diaries, July 1942 - Vol 3, NAID: 195486951, National Archives and Records Administration. ↩

-

The Jackson Advocate, “Negro Youths Prepare To Live Up To Glorious Marine Tradition”, 22 May 1943. ↩

-

The Omaha Guide, “Leathernecks Celebrate 1st Anniversary”, 4 September 1943. ↩

-

Henderson Daily Dispatch, “First Negro Marine”, 19 September 1942. ↩

-

“Alfred Masters Overseas Tour of Duty” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

Photograph of Marine Howard P. Perry at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, courtesy of National Archives: NAID: 535870, National Archives and Records Administration, link: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535870 (checked 13 January 2025). ↩

-

Alamy, Howard P Perry, the first African-American to enlist in the United States Marines Corps in World War Two 1942, Image ID: EX6JPE, link: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-howard-p-perry-the-first-african-american-to-enlist-in-the-united-84968982.html (checked 13 January 2025). ↩

-

Jonathan D. Sutherland, African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia (2004), 473. ↩

-

Sutherland, African Americans at War, 619. ↩

-

Sutherland, African Americans at War, 620. ↩

-

Jessie Carney Smith, Black Firsts: Groundbreaking events in African American history (2009), 448. ↩

-

Shaw, Henry I. Jr., and Ralph W. Donnelly, “Blacks in the Marine Corps”, (2002) 3. ↩

-

Guidebook for Marines (2009) 18. ↩

-

Jon T. Hoffmann (ed.), USMC: A Complete History (2002), 275. ↩

-

Courtesy of Alfreda Masters & Isabell Masters “Not For Myself But For Others”. ↩

-

War Department, TM 9-1320, War Department Technical Manual, Ordnance Maintenance, 75-mm Howitzers and Carriages, April 1944, 15. ↩

-

“How Alfred Became A Cook By Mary Ann Masters”, courtesy of Alfreda Masters. ↩

-

“Excerpts From An Interview With Charles L. Bryant, USMC, Retired, Age 72” By Alfreda Masters. ↩

-

“Excerpts From An Interview With Charles L. Bryant, USMC, Retired, Age 72” By Alfreda Masters. Bryant misidentifies the unit as the 51st Defense Battalion. ↩

-

Courtesy of Alfreda Masters. ↩

-

Shaw & Donnelly, Blacks in the Marine Corps, 25. ↩

-

“Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters Overseas Tour of Duty” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

“Alfred, The Cooks, And The Scrawny Japanese (Related By Alfred Dan Masters, Son)” (courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

“Charles Davenport, Gunnery Sergeant/Acting Master Sergeant, Recollections Of Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters, Excerpts From An Interview With Alfreda Masters” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

“Charles Davenport, Gunnery Sergeant/Acting Master Sergeant, Recollections Of Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters, Excerpts From An Interview With Alfreda Masters” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

“An Outline Of Family Togetherness And Isabell’s Goings, Comings, And Doings During Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters’ WWII Military Service (Sourced From Alfreda’s Baby Book And Isabell’s Autobiography)” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

“An Outline Of Family Togetherness And Isabell’s Goings, Comings, And Doings During Technical Sergeant Alfred Masters’ WWII Military Service (Sourced From Alfreda’s Baby Book And Isabell’s Autobiography)” (Courtesy of Alfreda Masters). ↩

-

Courtesy of Alfreda Masters. ↩